JUNE 2025

Human Factors Lessons for AI

Designing for human fallibility creates resilient systems; designing for perfection creates brittle ones.

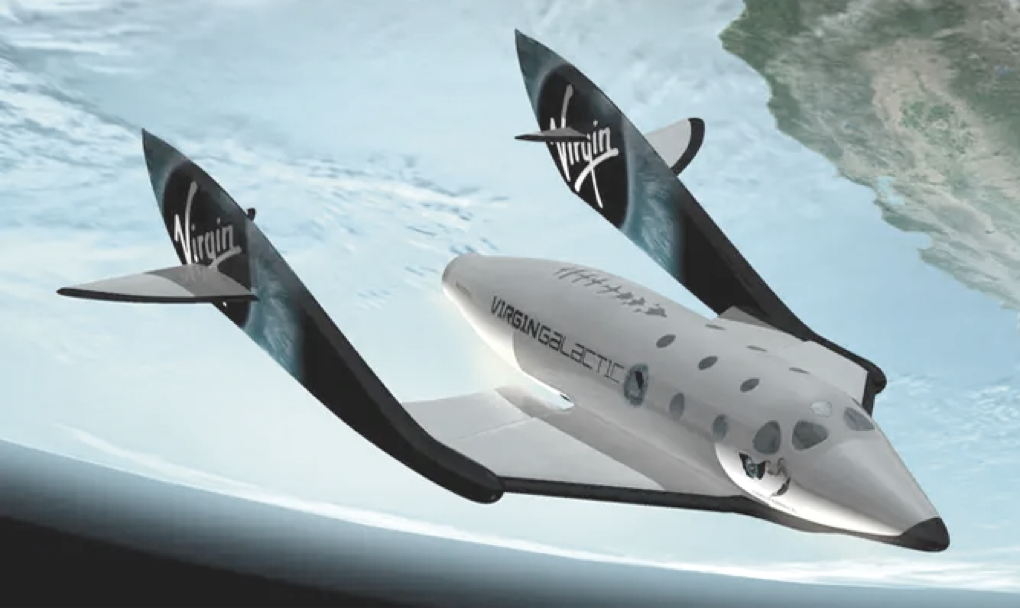

Technological systems fail when machine assumptions clash with human expectations. The aviation world offers case after case: the Virgin Galactic crash, for instance, where the error was not in the software, but in the design of the interface, the cognitive burden it placed on a pilot, and the lack of safeguards against predictable human error. A similar logic applies to AI. It’s not enough to ask what the system decided. We need to ask whether the person on the other side of the screen could reasonably understand it, challenge it, or override it.

AI isn’t static. It learns. It adapts. It gets things right for reasons we don’t always understand—and wrong in ways we may never predict. This is not software in the traditional sense. It’s a statistical system layered over dynamic data, often trained on opaque assumptions and optimized for goals that may or may not align with human judgment. And when these systems make decisions with serious consequences—clinical, legal, automotive, financial—the question becomes not just “Does it work?” but “For whom? In what context? And what happens when it doesn’t?”

Accountability frameworks reveal blind spots that technical teams may overlook and prevent applications that could cause broader societal harm.

The problem, increasingly, is that AI systems often provide limited explanations of their reasoning. They frequently recommend with insufficient context, make assessments while inadequately conveying their uncertainty levels, and can present outputs with apparent confidence that may not reflect their actual reliability-creating particular problems when their outputs are incorrect. And people, being people, often assume a confident machine is a competent one. They defer, comply, and automate the wrong judgment. Not because they’re lazy, but because the design encourages it. That’s not user error. That’s a system error.

Human factors anticipate these dynamics. It explores how

people interpret feedback, form trust, and recover from

mistakes. It insists that systems—especially powerful ones

—must align with human perception, cognitive limits, and

real-world workflow. It is designed for the human, not around

them. And it has decades of lessons to offer.

A, perhaps, underappreciated source of those lessons is

medical device regulation. In a world where machines

routinely interact with the human body—ventilators, infusion

pumps, implantables—people learned long ago that safety

cannot be retrofitted. It must be designed from the start,

tested under real-world conditions, and monitored over time.

Its framework—clinical validation, risk-based classification,

post-market surveillance—offers a sober, well-tempered

model for AI guidance.

It also offers a deeper insight: not all risks are equal. The

same algorithm that recommends a lunch spot in one

context might recommend a cancer treatment in another.

And while both may involve data and prediction, the

consequences—and required standards—are wildly different.

The principle here is proportionality: more power, more

oversight. That’s not bureaucracy. Just thoughtful and

responsible design.

And yet, traditional regulation hits a wall when systems can

change themselves. Medical devices are usually static. AI

systems can drift, retrain, and adapt. What worked in

version 1.0 may quietly mutate into something else in

version 1.3. The fix is not to freeze development but to build

a system of continuous accountability: performance tracking,

bias auditing, feedback loops, and clear thresholds for when

revalidation is needed.

That raises another awkward question: when things go

wrong, who’s responsible? The developers? The manufacturer?

The user? The AI itself? In the absence of clear guidelines,

accountability becomes a game of hot potato. A mature

regulatory framework would face this head-on—not by

blaming—but by building in traceability, auditability, and

shared responsibility.

Will this kill innovation? The medical device industry offers a

counterpoint: rigorous standards can coexist with innovation.

When the rules are clear, risk is matched to requirements.

The path to compliance isn’t paved with ambiguity. Good regulation doesn’t freeze technology. It disciplines it, channeling our ambition toward safety, transparency, and public trust.

Effective AI development requires integrating human factors and accountability frameworks as core design principles. These frameworks form the essential architecture that aligns our most powerful technological tools with human needs, values, and cognitive realities. The objective is to build AI systems that amplify human judgment, enhance decision-making capabilities, and establish trust through transparency and reliable performance.

The systems we create reflect our foundational assumptions about human nature, knowledge, and decision-making authority. Designing for human fallibility creates resilient systems; designing for perfection creates brittle ones. AI's potential will be realized through frameworks that prioritize human agency and understanding from the ground up.

David Taylor

David brings hands-on product design and research expertise to engineering and science teams, working closely to shape technology that adapts to people, not the other way around.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Accountability Framework Example

Excerpts from a Human Factors Validation study I conducted while working on a novel medical device. Such evalulation criteria may serve as a starting point for developing AI technology responsibly.

Data-Driven Design Decisions

Technical teams especially appreciate seeing that hard

data driving product decisions. In this presentation excerpt,

I report usability and risk issues uncovered during HF Validation testing.

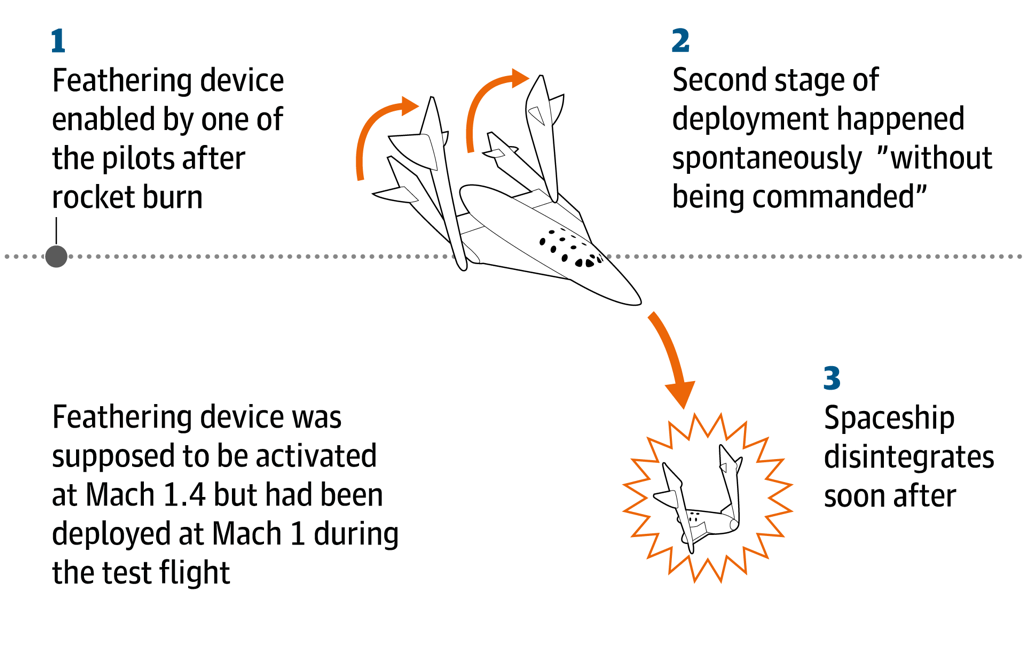

SpaceShipTwo’s two tail wings are supposed to move when the spacecraft hits a certain speed, a maneuver known as “feathering.” This repositioning helps to increase drag in order to slow the vehicle down for reentry. The co-pilot — who died in the crash — unlocked the feathering system early, doing so at Mach 0.92 instead of the intended speed of Mach 1.4. This triggered the feathering maneuver to occur prematurely, which ultimately caused the vehicle’s catastrophic structural failure.

A conditional inhibitor would have prevented premature unlocking, disallowing any unsafe procedures. The manufacturer said it did not consider the possibility that a pilot would unlock the feather prior to Mach 1.4.

MARCH 2022

Decline of the Screen

Is the screen interface dying? Not quite. But we’re at the threshold of transformation in how we interact with technology —and each other. Our relationship with digital systems has been mediated almost exclusively through screens and keyboards. This paradigm is beginning to crack, revealing glimpses of a future where the screens and keys become just one option among many, rather than the default entrypoint to the digital world.

Screen-Mediated Reality

Human-technology interaction is fundamentally

screen-centric. Whether through smartphones,

computers, tablets, or televisions, we engage with

digital information by looking at rectangular surfaces

that translate data into visual representations. This

model has shaped not just how we access information

but how we think about interface design itself.

Interaction, by its very nature, is a multi-modal

activity. Whenwe interact with each other, we engage

in complex patterns of turn-taking, verbal exchange,

and visual feedback. We read facial expressions,

interpret tone of voice, and respond to subtle

gestures. Human nteraction is fundamentally

dialogic—a dynamic exchange where both parties

actively participate in meaning-making.

Machine interaction, by contrast, has traditionally

been dominated by one party: the human. While not

a monologue, it lacks the fluid reciprocity of human

conversation. We click, type, and swipe, while

machines respond with predetermined visual feedback.

This asymmetry reveals the limitations experiences

brokered through vision—what we might call

eye-based or vision-based interaction. This includes

functional design (formerly known as UI design,

interaction design, or user experience design), all

unified under the broader umbrella of the graphical

user interface (GUI).

Sound has been present in this ecosystem, critically as a feedback mechanism—the click of a button, the chime of a notification, the beep of an error. Yet sound has remained secondary to the visual, a supporting player in the screen-dominated theater of human-computer interaction.

From Hardware to Natural Communication

Current interaction remains largely hardware-based: keyboards, mice, touchscreens. But we are gradually moving toward systems that leverage natural communication patterns: voice, gesture, and eventually, perhaps, thought itself.

The most significant innovations in this space are currently happening in accessibility technology. Driven by the need to create interfaces for people with different abilities, designers and engineers are developing novel, natural methods for interaction that often prove beneficial for all users. Voice control, gesture recognition, and eye-tracking technologies developed for accessibility are finding their way into mainstream applications, pointing toward a future where natural communication becomes the norm rather than the exception.

Voice or dialog-based systems that engage through patterns more closely resembling natural conversation where both human and machine participate in the exchange of meaning through language. Dialog has always been intrinsic to human relationships, and its integration into human-machine interaction represents a return to more intuitive, natural, and ultimately more human ways of engaging with digital tools.

The Next Frontier

After voice and gesture, the next frontier lies in direct brain-to-machine communication. This represents the ultimate collapse of the interface—a future where the barrier between human intention and machine response becomes so thin as to be nearly invisible.

Brain-to-machine interfaces will likely evolve into brain-to-brain communication, and eventually into brain-to-animal interaction, expanding our definition of what constitutes meaningful dialog. These technologies will challenge our fundamental assumptions about consciousness, communication, and the boundaries between self and other.

Conclusion: The Transformation Ahead

The screen interface is not dying—it is transforming. We are moving from a world where screens dominate interactions to one where they become part of a much richer ecosystem of communication possibilities. Voice, gesture, projection, and eventually direct neural interface will create new paradigms for human-machine interaction that are more natural, more intuitive, and more fundamentally human.

This transformation will require us to rethink not just how we design interfaces, but how we understand the relationship between humans and machines. As we move beyond the screen, we move toward forms of interaction that mirror the complexity and richness of human communication itself. The future of human-computer interaction lies not in perfecting the screen, but in transcending it entirely.

Mojo Vision Micro LED Contact Lens Enables Ambient Interfaces.

JANUARY 2022

Invisible Queue: Digital Orders Disrupt Physical Spaces

It happened again yesterday. I walked into Chipotle and found myself in what appeared to be a completely empty restaurant. No line. No customers waiting. For a brief moment, I felt that familiar spark of satisfaction—I'm the only one here, I thought. This will be quick.

As I stood at the counter, waiting to be served, the doubt crept

in. Are they even open? Not only was there no line of customers,

but there were no workers around either, at least not at the

service counter. The staff was presumably working somewhere

in the back. Growing frustrated, I imagined how I’d handle this

situation if were in charge. A simple, “Hey, welcome! I'll be right

with you!" would have made all the difference. Just letting me

know I’ve been seen, that I matter, would change everything.

But there was none of that. I stood there feeling disrespected.

Eventually, a worker emerged from the back, crossing to the

counter with purpose, grabbing a large bag of tortillas and disappearing without a word. Then it clicked. They’re not ignoring me—they’re busy fulfilling online orders, serving an invisible queue of customers. Sure enough, moments later, another worker appeared with an armful of

bagged takeout orders, confirming my suspicion. The restaurant wasn't empty at all. It was bustling.

Awareness Problem

This shift from in-person to remote ordering is creating genuine confusion and frustration. As customers in physical spaces, we've always relied on visual cues to navigate our experience. How many people are in line ahead of us? How busy does the place look? Should we stay or find somewhere else? These environmental signals help us make informed decisions about how to spend our time. When those cues disappear, we lose our ability to gauge our place in the system, or even whether we're part of a system at all.

This disconnect creates misunderstandings that can quickly escalate. I wasn't particularly rushed that day, so my frustration remained mild. But I could easily imagine a different scenario—someone in a hurry, having a bad day, or simply less patient than I was feeling. They might have walked out angry, never realizing they were actually being served, just not in the way they expected.

Context vs Social Contract

During high school, I worked as a busboy at an upscale restaurant where the maître d' had a simple but powerful philosophy: "Guests are coming into our house. We are the hosts. Treat them with care, make them feel welcome.” In other words, anything not directly tied to the guest experience? Put it on hold. And show presence.

That stuck with me. I expect that level of attentiveness when I walk into a store or restaurant and suspect I'm not alone. People carry an intuitive sense of what good service should feel like. There's an unspoken social contract

—when we enter a business, we expect to be acknowledged, to understand our place in line, and to have some sense of how long we'll be waiting. Is that contract fraying? Are we entering into a new one, where context is ever more ambiguous and feedback is an ever more necessary lubricant?

Systems and Trust: A Need for Orientation

No matter the space, physical or digital, people depend on, and expect, basic information being available: Where am I? What's my status? What are my options? And perhaps most critically: How long will this take? Without clear answers to these questions, people feel lost. They feel disrespected. In some cases, they feel cheated. The absence of feedback doesn't just create inconvenience—it erodes trust. When people feel comfortable—when they feel seen, informed, and oriented within a system—they make better decisions. They stay calmer. They're more likely to trust the process, even when things don't go exactly as planned.

Service environments are fundamentally systems, whether it's a restaurant, a mobile app, or a drive-thru. If people can't understand how the system works, or if they can't read the signals it's sending, trust breaks down. And once trust is broken, even small problems feel like major failures. The challenge for product developers is ensuring that people always know where they stand. There needs to be feedback, a sense of progress (or honest acknowledgment of delays), and regular confirmation that the system is working as intended.

The Path Forward

So how do we provide meaningful feedback in these hybrid service environments? Do people need help navigating spaces where the traditional social cues have been disrupted by digital ordering? The answer might involve rethinking our assumptions about what constitutes good service design. Do we need status displays showing approximate wait times? Protocols for acknowledging in-person customers is most certainly needed, especially if staff are primarily focused on online orders. The cues we have traditionally relied on for awareness are no longer enough. The business that clearly communicates with its customers will continue to have them.

What's clear is that the old rules no longer apply. We need new ways to help people know where they stand. Without them, we're left with more moments like mine at Chipotle—standing in the middle of what appears to be an empty restaurant, wondering what just happened and whether anyone even knows we're there.

The solution isn't to abandon digital ordering or return to purely physical service models. Instead, it's to thoughtfully bridge these two worlds, creating systems that serve both visible and invisible customers with equal clarity and respect. Only then can we restore the trust that makes good service possible.

Chipotle: the restaurant wasn’t empty at all.

OCTOBER 2017

The Volume Hunt

It took me about fifteen minutes to figure out how to turn the volume down in my dad's new Audi. Fifteen minutes. To adjust the volume. Let that sink in for a moment.

The Razzle-Dazzle Problem

Let me paint the picture: I’m in an unfamiliar car. The

radio’s too loud, so I want to turn it down. Dead simple

task. But accomplishing it was not. At all. Instead, I'm

confronted with a large generic knob, that apparently

does everything, masquerading as a user interface. Do

I need a PhD to navigate this thing? A PhD in what—

automotive interface design? If I wanted to take the

time, I could probably figure it out, but to turn the

volume down? Come on, Audi! The whole idea of

designing an interface is to enable productivity.

Minimize errors. Enhance performance and comfort

even. Why throw complexity in front of me when I just

want to turn down the volume?

Adaptation Burden

The interface becomes more logical and relevant the more you drive the car, I'm told. Audi has presumably identified everything I need to do, will do, must do, and has provided what they consider optimal, efficient and safe ways to do them.

Fundamental goals and tasks may not have changed much, but the methods to accomplish those them have been completely transformed.

Cars have moved well beyond basic functionality, yet there are increasingly fewer functional affordances like the knobs, pulls, buttons, and sliders we once relied on. The physical and perceptive that enabled us to crawl the dashboard to adjust the radio or tune the air conditioning while keeping our eyes on the road have given way entirely to esoteric workflows that demand constant visual cognition. People are not machines. We don’t speak digital.

More than ever, systems need to prioritize the human perspective. People need advocates throughout the development process ensuring that products are designed with the needs, abilities, and limitations of users in mind. Audi expects me to adapt to the car. Shouldn’t it be the other way around?

The Audience Question / “Decline of being… into merely appearing”

Who is this interface actually designed for? The editors of Motor Trend magazine? Wired magazine? Is it designed for the person actually sitting in the driver's seat? Perhaps the target isn’t the driver at all —not the frequent driver, the occasional driver, or the one-time test driver. Or passenger for that matter. It’s for the would-be driver. This is interface as spectacle, where the imagined experience (of the consumer/prospective buyer) has supplanted genuine human interaction. The goal isn’t providing utility, convenience and comfort. It’s to appear to provide it.

The Fundamental Question

Let me return to the beginning: why should it take fifteen minutes to figure out how to turn down the radio in a new car? This isn't about being technologically challenged or resistant to change. This is about fundamental usability principles being sacrificed for the sake of looking sophisticated or futuristic.

We've created interfaces that prioritize appearance over function, that assume users will invest significant time learning systems for basic tasks, systems that seem designed more for showcasing technological capability than for serving the actual needs of the people using them. In the pursuit of innovation, we've forgotten that the best interfaces are invisible—they’re adaptable and get out of the way, letting us accomplish our goals. Fifteen minutes to turn down the volume. That's not progress.

Audi’s Multi-Media Interface (MMI) Knob

JULY 2017

Prototype to Tell Stories

Mocking up representations, even crude concepts to

refined designs, affords the opportunity to challenge

assumptions and make adjustments before all of the

gears of the business are in motion. The experienced

entrepreneur seizes opportunity to use mockups and

their evaluation as critical to challenging the viability

of the product and indeed even the business plan.

Engineering will use mockups to explore the

specifications for what the real system will become.

Furthermore, having a tangible representation of

what is often still an idea the team’s collective mind,

keeps everyone on track and the project focused.

As a designer, I’ve experimented with prototyping

for projects across a diverse range of industries to

effectively demonstrate and validate concepts. An

effective customer pitch, for novel products or

technologies such as smart packaging for example,

buttressed by prototypes, can draw your audience

into an experience, the specific experience you want

them to have that will result their what you’d ideally

like them to do afterwards. In my experience, the most effective way to demonstrate sensor-enabled smart labels as the cold chain logistics game-changers they are, is theatre; telling a story using prototypes paints the vivid picture of the future for an audience. RFID readers that monitor conditions like temperature and humidity in real time across the logistics chain? I’ll show you, and in a context relevant to your business or industry.

Printed electronic labels and packaging prototypes were successfully demonstrated at IDTechEx. In addition to witnessing our demo, users could easily scan the bottles themselves and see the real-time updates on a nearby dashboard.

Smart packaging is an exciting area of interest, one that has the potential to revolutionize cold chain logistics, as well as retail in general. The working prototype was an important ingredient in communicating our vision for smart packaging to a broader audience.

“Everything that was directly lived has moved away into a representation.”

Guy Debord suggests that as the spectacle culture grows, the products that are produced lack originality. Consumers get so caught up in the hype and the imagery that they forget to deeply analyze the product to see if it is worthwhile.

MARCH 2017

Working with Proxy-Prototypes

Rapid inquiry using proxy prototypes helps

quickly reveal beliefs, habits, biases and expectations, that shape product goals and requirements.

What are proxy-prototypes?

• Quick, low investment method to evaluate the value of concept;

• Test hypotheses around customer experience and business value;

• An early best guess at a viable product;

• Don’t necessarily need to be functional in order to be effective;

• Designed quickly (2-days to 2-weeks) and deployed with real users;

• Employ minimal novel technology, but strong user stories;

• Findings collected from in-depth ethnographic pre/post-interview;

• Disposable; make way for more.

Purpose

1. Observe the world; understand human and business problems.

2. Create hypotheses about customer value and how to create it.

3. Generate idea spaces to test hypotheses;

4. Deploy with potential users for extended periods (1-2 weeks).

5. Debrief study participants, recording observations, learnings.

6. Evaluate hypothesis based on participant feedback.

7. Revise and repeat.

Clay proxy-prototype use for observing grasping and gesturing mechanics.

Participant handling a proxy-prototype standing in for an actual product.

PROXY-PROTOTYPE

As simple as possible, usually with a single main function and two or three easily accessible functions.

PROTOTYPE

Many layers of functionality to address a range of needs, not all of which may even be implemented.

Open-ended. Users should be encouraged to reinterpret them and use them in unexpected ways.

Focused as to purpose and expected manner of use. Focused as to purpose and expected manner of use.

Open-ended. Users should be encouraged to reinterpret them and use them in unexpected ways.

Focused as to purpose and expected manner of use. Focused as to purpose and expected manner of use.

Not about usability and not changed based on user feedback. A deliberate lack of certain functionality might be chosen in an effort to provoke the users.

Usability is a primary concern and the design is expected to change during the use period to accommodate input from users.

Collect data about users and help them (and us) generate ideas for new technology.

Can collect data as well, but this is not a primary goal. Can collect data as well, but this is not a primary goal.

Introduced early in the design process to challenge pre-existing ideas and influence future design.

Appear later in the development process and are improved iteratively, rather than thrown away. [Based on Hutchinson et al, 2003]

Sanitary pad that identifies and treats conditions such as hormone imbalance and infection. Photo courtesy of Siqqi Wang.

FEBRUARY 2017

Designing for Emotional Effect

Everything around us has been designed in some way and all design ultimately produces an emotion. We experience an emotional reaction to our environment, moment-by-moment: a like or a dislike, elation, joy, frustration. Concepts validated by target users can help identify the powerful motivators that lead to making meaningful connections.

Response > Emotion

Experience Designers strive to design usable,

functional experiences but to also generate a certain

emotional effect for the user and try to maintain it

throughout the use experience. Design for Emotion

concentrates on how a product or interaction affects

users. It is a moment-by-moment journey with

occasional pauses. A continuum operating on ones

visceral, behavioral and reflective functions

Emotions change the way the brain operates;

negative experiences can prod us to focus on

what’s wrong; they narrow the thought process,

potentially making someone feel anxious and tense.

Feelings of frustration and restriction can grow into

extreme emotions, like anger, an emotion not typically associated with a successful product or company. Positive experiences elicit pleasure and the sense of security or validation that are characteristic of successful products, their repeat use and brand loyalty.

Customer experience strategies need to include designing for the entire human experience. User research and product testing are used to effectively set up and gauge the emotional effects of a product or service on users. Touch-point mapping, for example, helps to identify obstacles where users may become frustrated and drop out of an encounter, or become pleased and successfully complete the encounter and return for more. A project I co-led to integrate AOL’s single sign-on feature into Amazon’s purchase flow, circa 2000, comes to mind. Together with Amazon’s design and engineering teams, we probed each discrete

decision point within the authentication flow to reveal weaknesses.

Tactics likes these help designers and product managers better understand customer motivations, anticipate user behavior and better design products. Genuinely seeing what’s right in front of you can be vital to delivering an ideal customer experience and competitive advantage.

The Turbo Tax mood question: an empathy tactic to foster trust, loyalty? Systems may overtly or covertly monitor sentiment to determine tone and workflow that inspire comfort and efficiency.

Copyright ©2025 David C. Taylor. All rights reserved.